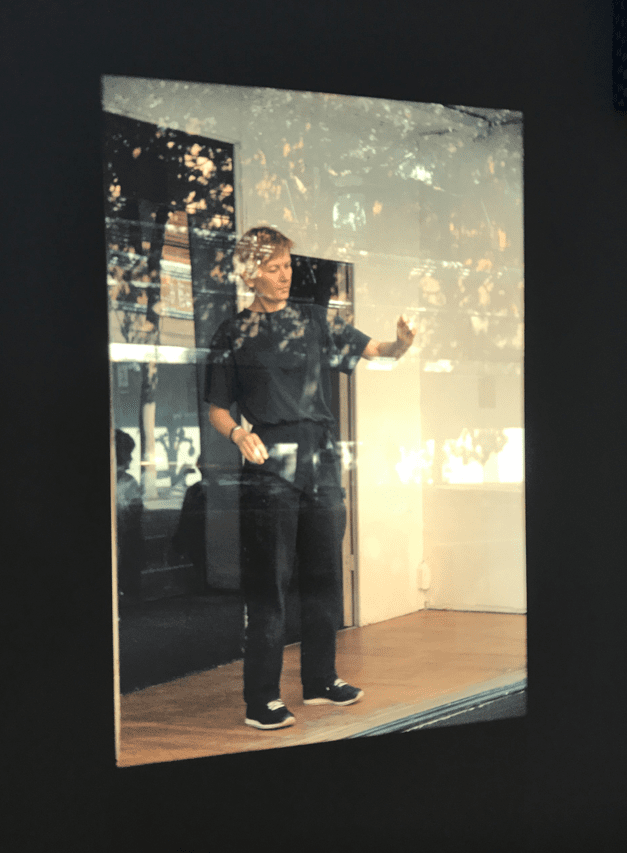

At the entrance to Edith Dekyndt’s second solo exhibition, Blind Objects, a person stands in front of the gallery window, slowly wiping a mars plastic rubber across the glass. It is a reiteration of a gesture first made by the artist in Vancouver twenty years ago. Then as now, this activity of erasure isn’t likely to succeed. Unlike removing a mark from a drawing, or deleting an error from a document, it is impossible to ‘erase’ a view from a window. The person will be incapable of obscuring the glass, and unable to blight out the buildings and the people passing behind it. We can take the gesture to be a means without an end. This introspective concentration and repetitious mark-making, one following the next in a slow rhythm, confronts both the individual and the viewer with the present moment, and the essential fact of constant change. At the same time, we are presented with what is enduring, real, and beyond the control of one individual.

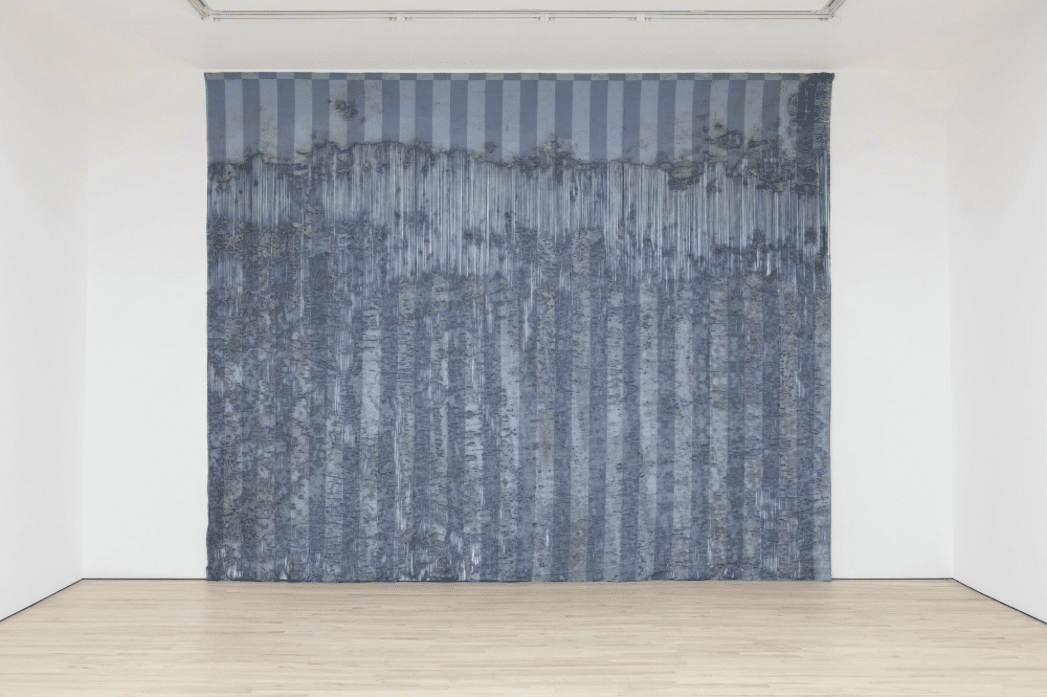

Inside the gallery, new sculptures involve temporal processes that are not immediately visible, but are known to happen. For this reason, they are mostly forgotten, or considered too enigmatic to be perceived without such intricate or delicate webs as those Dekyndt has set in place to bring them to light. On the far wall of the gallery hangs a swathe of blue and white fabric that had been buried underground for a period of six months, allowing minerals, plant roots, humidity, bacteria and insects living below the François Pinault residency in Lens, France, to nestle into it. Layered into the earth in a vertical zig-zag arrangement, parts of the cloth were only lightly gnawed, while others have been destroyed completely – presumably those lodged in the lowest and least accessible depths of the soil. Lens is a mining town, and the surrounding areas in the North of France are known for embroidery, two forms of industry that Dekyndt had in mind while making the piece.

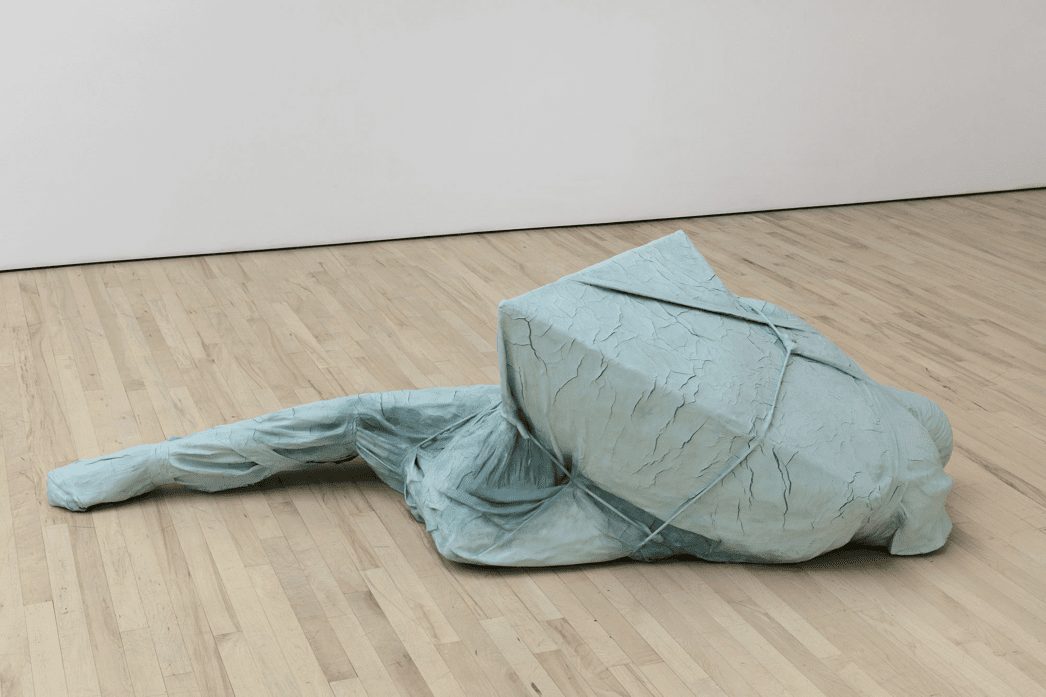

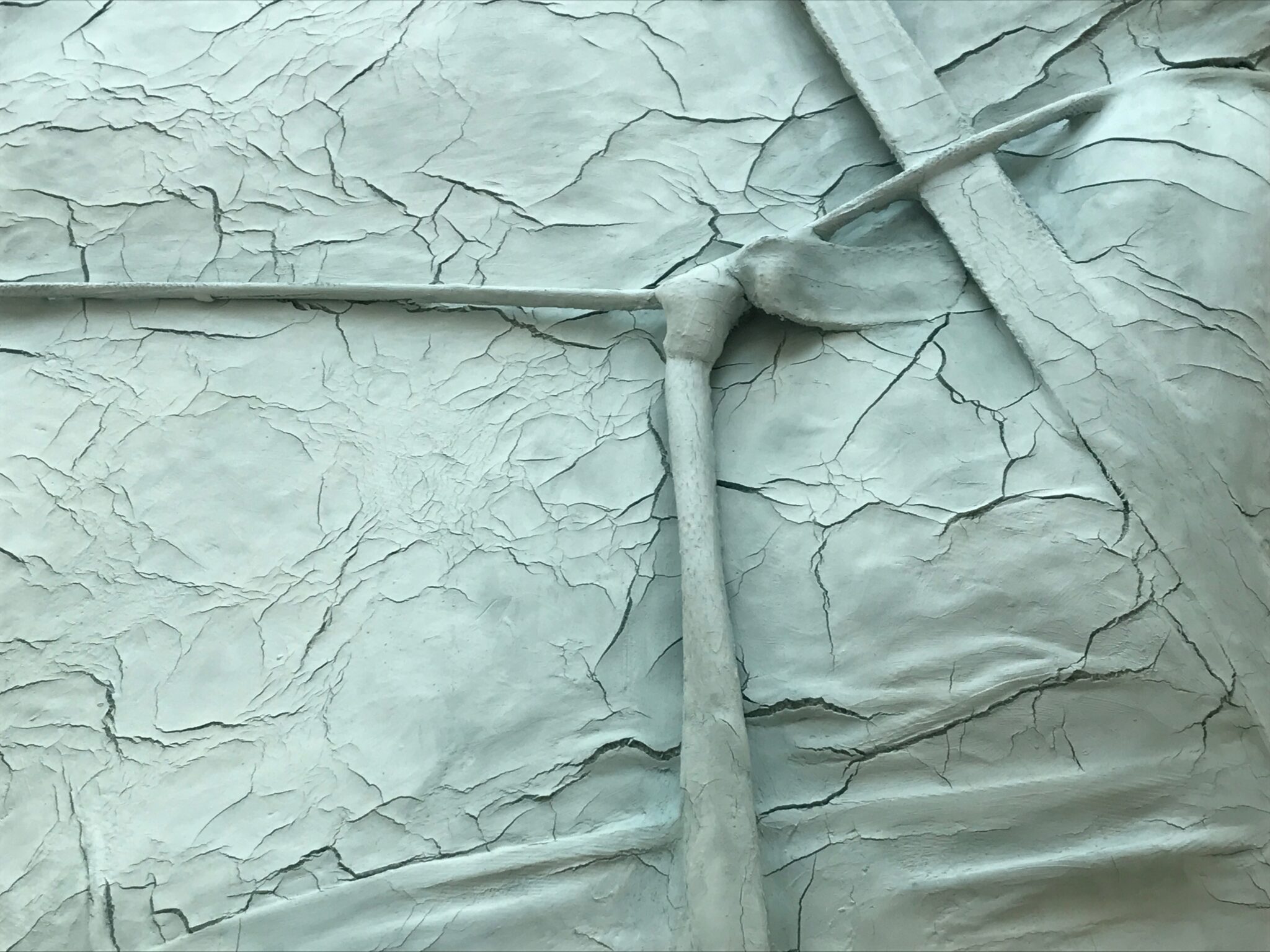

We could say Dekyndt has tuned her practice to the principles of physics and chemistry because of a persistent ‘why.’ A cloud soaks up moisture from the sea like a sponge – why? The rain falls on the ground and waters the soil. Why? Plants, through a sensitive process of capillary action, draw hydrogen from water and continue to grow. The ‘why’ will continue, however, passed the point when the question can be answered. Beyond this point, the world is mysterious, and its most secretive aspects are hidden from view. So the scope of Dekyndt’s inquiry expands to include notions of material as well as generational change, youth, and age. A bulky, oblong sculpture in the center of the gallery is based on a Malian ceremony in which a shaman coats a devotional object in ritual mud. The identity of the item is only known by the giver and the shaman. Underneath Dekyndt’s blue clay are layers of packing blankets and rope, in which she has hidden numerous objects: both from the artist’s home, and from her mother’s. Both of them are in the process of moving after living in their respective homes for decades (Dekyndt had occupied her house for 25 years, had reared children and developed a successful art practice within it. Although subtle it is possible I heard a faint catch in her throat when she talked about the move). Perhaps the toughest part of change is that it is so difficult to see it happen – only after a move, or some event, are we able to raise our heads up out of the stream and look back. Dekyndt’s new works, and the recreation of the ‘erasing’ gesture, are poignant and understated reminders to widen our perception and catch what we can of the process as it is happening.