By observing the plants on his desk day in, day out, Cleve Backster discovered that they reacted to his presence, his mood and his emotions. In the 1970s, if not earlier, he had succeeded in developing detectors which can sense presence. He worked with sensors attached to the stems and leaves of houseplants, conducting numerous experiments with various living organisms including crabs and yoghurt. Working for the FBI, he was extremely adept at detecting deceptions. (1)

Edith Dekyndt

L’ennemi du peintre, 2010–2011/2020

After studying Visual Communication and Art, during a trip to Italy Edith Dekyndt began investigating the treatment of light in the frescoes of Piero della Francesca, cooperating with various architects. Unsatisfied with architecture’s task of prescribing the form of human habitation, a few years later she turned to other studies which, over time, led to her characteristic artistic practice. Since taking part in the Venice Biennale in 2017, her work has been known to a wide international audience.

In her early works, Dekyndt’s art assumed a decidedly experimental observer position. The works consist of visualisations and experimental set-ups dealing with physical phenomena. She captures the behaviour of materials in certain situations in videos and/or photographs, which she leaves unchanged. They are matter-of-fact documents of physical (for example, a plastic bag blown around the countryside by the wind, or the behaviour of raw egg white in water) and/or chemical phenomena (the behaviour of a soap film stretched between hands’ fingers at different temperatures). Two complementary strands of Dekyndt’s work are already evident in these works dealing with ‘everyday’ phenomena: on the one hand, the systematic, objective approach in an almost scientific sense and, on the other, the discovery of a poetic dimension intrinsically linked to the perception of these phenomena.

For about two decades now, the artist has been enlarging her oeuvre, focusing above all on energies that take effect at or beyond the boundary of human perception and always in the dynamic context of human beings and nature. Consistently reduced in terms of form and positioned with great precision in three dimensions, her works allow us to experience many different kinds of processes (for instance the oxidisation of silver on curtain fabrics), or they refer to historical, sometimes political contexts (for example recently at the Kunsthaus Hamburg to the economic activities of a major port). Her current work might be described as the visualisation or making-perceptible of a host of transformative processes.

The installation L’ennemi du peintre is among her most complex works to date. It was made in 2011 as a commission for the 5th Biennial of Moving Image Contour 2011 in Mechelen, Belgium, and has since been exhibited in changing constellations at different venues. The presentation at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein is another variation on this work.

The starting point of the installation is a bouquet of white roses (Rosaceae rosa) in a simple, transparent vase on a table in the room. Although the table is not at the centre of the room, the narrative of the installation develops from here. This deliberate non-reference to the hierarchical order of geometry already points to Dekyndt’s method of developing her research and analytical findings in free, associative and often intuitive arrangements. For all the references to scientific findings formulated and cited in the various elements of the installation, the work exhibits a surprisingly poetic autonomy.

The table with the roses is encircled by seven ‘points of interest’ in the room, with accompanying texts collected in an audioguide. Five of the ‘points of interest’ address the way various scientific disciplines approach the question of how similar plants and humans are and what communication between the two might look like. Beginning with documents from experiments designed to investigate the emotional reactions of plants to their surroundings and non-chemical practices of plant stimulation on different continents, the viewer comes to studies of how plants generate sounds and frequencies in protein synthesis that can, in principle, be heard by human beings.

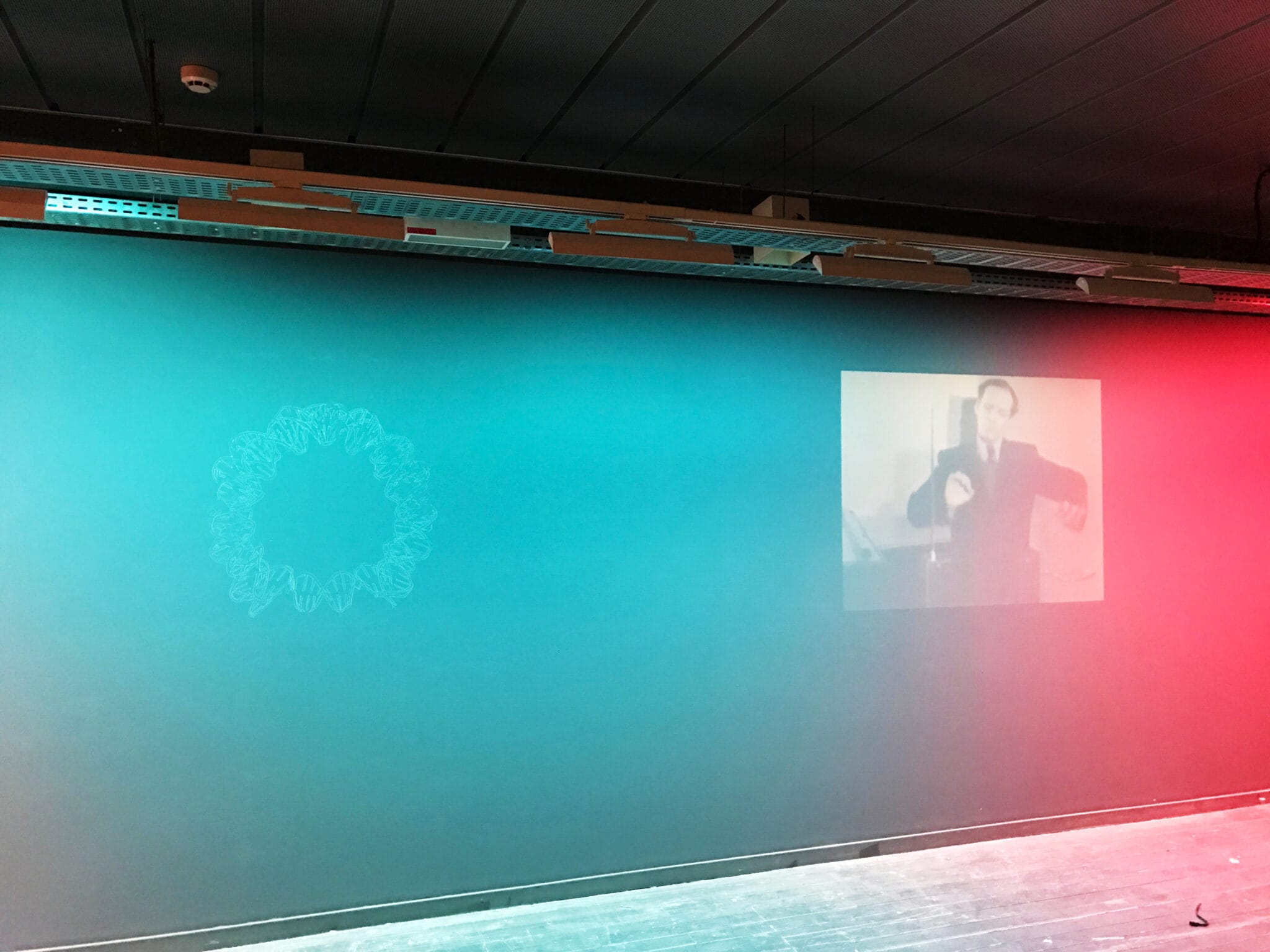

At this point in the ‘narrative’, Dekyndt leaves the documentary realm, joining forces with a composer to translate the plants’ waves into a musical score. She then had this score performed by a musician on a theremin and recorded. This is an electronic musical instrument invented in 1919, consisting of two antennas it produces sounds controlled by a musician who does not touch the apparatus. The player’s body acts as an electrical conductor. Its inventor, physicist Lev Sergeyevich Termen, went on to develop the Illuminovox, which further translates the sounds of the theremin into colours that vary between the two extremes (infrared and ultraviolet) depending on pitch. Finally, the artist turned the score of plant sounds performed by the musician into a video based on the principle of the Illuminovox.

Walking through the installation, the viewer’s initial impression is one of an unorthodox presentation of the history of science. At the same time, the rarely posed question as to the similarities in the behaviour and genetic structure of human beings and plants, the reference to a J. G. Ballard short story from 1956 (in which people have learned to understand the language of plants), and particularly the theremin’s unusual sounds all contribute to a sense of an ‘unreal’ atmosphere. This is augmented by the title of the installation, which at first seems completely at odds with its underlying question: The Painter’s Enemy.

Is this ultimately an almost syncretic defamation of painting? In French, ‘L’ennemi du peintre’, or ‘Le désespoir du peintre’ [The painter’s despair] is the common name for the rockery plant Heuchera known for its countless little red flowers. The artist often uses such puzzling titles, which usually add another level of meaning to her works. In fact, this is not so much about the plant itself but rather the fact that the title points to a classical technique of art: painting. If we look at the installation again from this vantage point, we see another narrative unfolding, one that goes from the classical genre of the still-life (the roses in the vase) to the time-based ‘painting’ of the Illuminovox. Dekyndt leaves open the question whether a painting of roses in a vase or the synthetic painting of the Illuminovox has the greater degree of reality.

Friedemann Malsch

(1) From the audioguide text, track 1, of L’ennemi du peintre.

Exhibition places

-

Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz

6 September 2020 — 17 January 2021

Website -

Le Fresnoy, Studio national des arts contemporains, Tourcoing

4 March — 7 May 2017

Website -

Fonds régional d’art contemporain (Frac) de Bourgogne, Dijon

31 October — 3 April 2016

Website -

Fonds régional d’art contemporain (Frac) de Franche-Comté, Besançon

21 June — 21 September 2014

Website -

Le printemps de septembre, Toulouse

23 September — 16 October 2011

Website -

Contour 2011, 5th Biennial of Moving Image, Mechelen

27 August — 30 October 2011

Website